Blog: The Super Bowl’s undeniable connection to nationalism

“The Haitch” with Aubtin Heydari.

February 3, 2014

This year’s Super Bowl, as one of America’s primary cultural events, proved to be a shining example of the emerging state of American media. From the opening performance of the National Anthem to the maelstrom of commercials, we are conditioned to this sense of patriotic obedience. We are taught and expected to take part of this ritual of nationalism. I would like to clarify that I am not condemning taking pride in one’s country or having respect for the armed forces, rather I am merely examining the extent to which these things occur. Ultimately, Super Bowl Sunday is an affective phenomenon, one designed to trigger basic responses from us based off emotionally pandering to the common denominator.

I noticed this during the halftime performance; Prior to Bruno Mars forgettable performance, several people I follow on Twitter were lambasting Mars for being unoriginal, repetitive and generally a bad pick as the esteemed halftime performer. Once he started singing “Just the Way You Are,” the tone completely changed. There was a touching montage of troops overseas telling their families they miss them. Suddenly Twitter, including several people who previously tweeted that he was trash minutes prior, blew up over how talented of a musician he was because of his ‘respectful’ performance. I am aware that some of these people might not have flip-flopped their opinion, but the number of people I did see who instantly changed their tune concerns me.

All Mars had to do to win the admiration and respect of these people was to have a 15 second blip about armed forces. It seems that this is the state of American media; dozens of the ads last night were centered on ‘respecting the troops.’ I think this is less a matter of actually honoring those who serve, but rather about generating a particular type of citizen. It associates the product with national identity, and therefore national duty. More importantly, it creates an emotional response that changes the way we perceive and remember the commercial. The commodification of the Armed Forces experience is not different from the cute puppy or attractive female commercial; they want to make us feel good so we buy the product. This ability to sway the opinions of millions of people by showing 10 seconds of generic staged military reunions is immensely problematic; we have become blindly obedient to militarism.

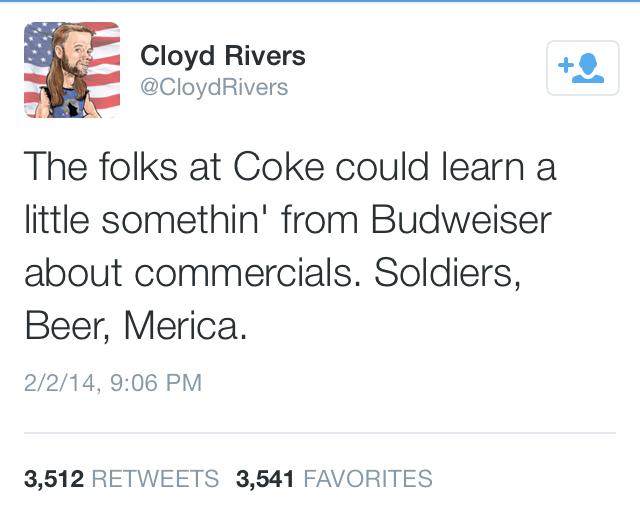

In juxtaposition to this is a Coke commercial that focused on the diversity of America. It featured an LGBT family and ethnic families singing “America The Beautiful” in different languages. Unfortunately, the commercial sparked outrage amongst the “speak English!” crowd of America. This form of nationalism, focused on diversity and plurality, seems to still be unacceptable because it challenges the traditional notion of what nationalism means: white, hegemonic and militaristic patriotism. We don’t want to see diversity, equality, unity or fairness, we want is to be secure and belong to something specific and concrete, not multifaceted and complicated like a multicultural society. Prominent Twitter parody ‘redneck’ figurehead Cloyd Rivers made a remark about how Coke had something to learn about America from Budweiser (which had a commercial stereotypically featuring troops and Armed Forces), which shows the degree to which cosmopolitanism is considered un-American. My argument is not that nationalism is bad, it’s that the Super Bowl shows that there is only a very specific form of nationalism that is acceptable.

All it takes is a few clips of troops being reunited before every unrelated performance or advertisement to psychologically condition someone. These commercials never alleviate any serious problems those in the Armed Forces face, but it lets us feel a little better about ourselves knowing we felt like it could for a second. The Super Bowl as a whole is designed to make us subscribe to this antiquated understanding of national identity. Being an American is not about equality of opportunity or liberty and justice for all, it’s about respecting troops for ten seconds and then returning to our beers. Besides, it’s a lot simpler that way.